For Augustine, the sacred Scriptures disclose a coherent narrative about the world and human history, the central drama of which is the onward march of the city of God to its heavenly end. However, as Augustine discusses in great detail throughout The City of God Against the Pagans, Scripture’s language not only discloses literal or historical meanings, but there are also hidden spiritual meanings within the historical record. These types, allegories and symbols are not merely literary flourishes, but they form the structure of the narrative by relating lower things to higher things, and earlier things to later things.

In this paper, I will focus upon Augustine’s treatment of the brief biblical record of Cain and Abel, and consider how Augustine’s use of typology and allegory helps him to relate this little episode to many of his other points throughout The City of God.

Typology or allegory?

There is sometimes a distinction drawn between the concepts of typology and allegory. Michael Cameron helpfully summarises the conventional wisdom on this apparent distinction:

Scholarly opinion seems to favor seeing the terms as competitors, viewing “allegory” as arbitrarily denigrating or dismissing the literal historical base of the word or event that, by contrast, “typology” respects. “Typology” […] describes the figurative link forged between narrated biblical events, something that appeals to the modern preoccupation with historically verifiable accounts. (Michael Cameron, Christ Meets Me Everywhere: Augustine’s Early Figurative Exegesis)

However, as Cameron goes on to claim, this apparent antagonism between the terms would have made little sense to Augustine. This is seen in The City of God itself: Augustine uses the term “allegory” not only for “upward” relationships between earthly and spiritual, but also in some places for the “forward” relationship between one historical particular to a later one. For example, in Book XVII chapter 3, Augustine writes:

when we read of prophecy and fulfilment in the story of Abraham’s physical descendants, we also look for an allegorical meaning which is to be fulfilled in those descended from Abraham in respect of faith. (St Augustine, Concerning the City of God Against the Pagans)

Accordingly, I will use the terms “allegory” and “typology” fairly interchangeably.

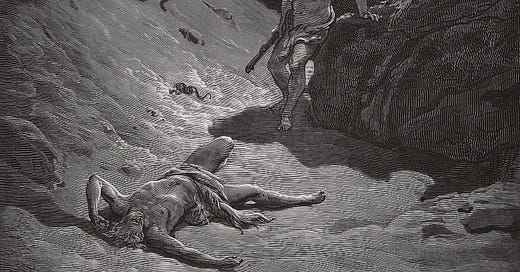

Cain and Abel

Let us briefly review the outline of the narrative of Cain and Abel in Genesis 4: After Cain, the older son of Adam and Eve, makes a tribute offering that fails to be accepted by the Lord, he murders his younger brother, Abel, whose own offering was pleasing to the Lord. The Lord then casts out Cain from his presence as a vagabond; Cain then establishes the first city. Adam and Eve give birth to another son, Seth, whom Eve receives as a replacement for her murdered son Abel. Amidst Seth's descendants are those who call upon the name of the Lord.

Diptychs and eschatology

Before any consideration of the specific features of the two main characters, Cain and Abel, the fact that there are two main characters should not be overlooked. The author of Genesis sets Cain and Abel against each other as in diptych (a two-panelled artwork) so that their various similarities and differences can be seen more clearly. This “diptych” aspect of the narrative provides the basic framework for all the other allegorical elements.

In Book XV, Augustine quickly relates the Cain/Abel diptych to the work’s titular “diptych”, namely, that of the city of God against the pagans:

Now Cain was the first son born to those two parents of mankind, and he belonged to the city of man; the later son, Abel, belonged to the City of God.

The diptych of the two sons in the Cain and Abel narrative together with the diptych of the two cities invites Augustine to make connections to other diptychs in The City of God, such as those between earth versus heaven, the seed of the flesh versus the seed of the promise, the Jews against Christ.

Many of these diptychs, however, have a further element that requires the unfolding of time to appreciate more fully. Augustine’s allegorical treatment of Cain and Abel is attentive not only to the story’s “upward” symbolism, but also to its “forward” symbolism over time. This is important for The City of God, because the two cities are not simply two parts in a timeless “yin-and-yang” system. They are two characters in a drama, and the true character of each city can only be seen over the course of the narrative.

In the previous quote, Augustine noted that Cain was the “first son born” to Adam and Eve, and that Abel was “the later son”. There is in these passing details an implied eschatology: Cain first, then Abel. Augustine relates this to the teaching of St Paul in 1 Corinthians 15:46, concerning eschatology and resurrection:

It is our own experience that in the individual man, to use the words of the Apostle, ‘It is not the spiritual element which comes first, but the animal; and afterwards comes the spiritual’ […] When those two cities started on their course through the succession of birth and death, the first to be born was a citizen of this world, and later appeared one who was a pilgrim and stranger in the world, belonging as he did to the City of God.

The natural-to-spiritual movement is the basic temporal/eschatological movement for Augustine. The city of God thus has a movement throughout history on its earthly pilgrimage towards its heavenly end, whereas the earthly city fails to make this progression.

Significance of names

Augustine also draws allegorical meaning from is the names of the biblical characters. It should be noted in the first place that Augustine’s etymologies of biblical names is limited somewhat by his relatively weak grasp of Hebrew. Nevertheless, some of his etymologies are supported by better readers of Hebrew, and these at least are worth considering.

Augustine relates the name Cain to “possession”. This detail of the narrative supports Augustine’s relating Cain to the citizens of the earthly city, who are

those who have supposed that the Ultimate Good and the Ultimate Evil are to be found in this life […] all these philosophers have wished, with amazing folly, to be happy here on earth and to achieve bliss by their own efforts.

In stark contrast to Cain and his earthly hopes are the hopes of Abel and his successor Seth. (It is important to tie Abel and Seth together as the first and second stage respectively of the eschatological movement of the city of God, for reasons to be discussed below.) Augustine draws this in part from their names, which respectively mean “lamentation” and “resurrection”.

Later expositors such as John Calvin have noted the etymological relationship between Abel and the term “vanity”, or hebel in Hebrew (see John Calvin, A Commentary on Genesis). Augustine’s relating Abel’s name to lamentation, however, is not without merit: “hebel” is an onomatopoeia, and its repetition throughout the book of Ecclesiastes is suggestive of the Qoheleth’s heavy, weary sighing as he laments the vanity of man’s mortal life.

There is some difficulty in Augustine’s etymologising of Seth as “resurrection”. James B. Jordan translates Seth’s name as “appointed” (James Jordan, Trees & Thorns). This reading of the name seems to emphasise that he is appointed to replace Abel, rather than specifying resurrection as the form that appointment takes. While Augustine does not connect the appointment concept to Seth’s name, he does recognise such an appointment when he writes: “Seth was to prove to be the son to carry on his brother’s holiness”.

The names of Cain and Abel are evocative of the fundamental conflict between the two cities, whereas the names of Abel and Seth (at least, in Augustine’s etymologising) are evocative of the eschatological fulfilment that Seth provides relative to Abel.

Sacrifice & martyrdom

The narrative of Cain and Abel is a story of bloody sacrifice. Augustine’s discussion of sacrifice in connection to Cain and Abel should draw the reader’s mind back to the extensive discussion of sacrifice throughout the previous books of The City of God, particularly in Book X. For Augustine, the true sacrifice is humaniform: Christ offers up to God a living human sacrifice, consisting of himself as head and his people as his body:

the Church, being the body of which [Christ] is the head, learns to offer itself through him.

How do Cain’s and Abel’s sacrifices relate to this humaniform vision of sacrifice? Augustine makes the key distinction between Cain’s and Abel’s respective sacrifices in that the former’s was “not rightly divided”. Augustine’s reading of this obscure Hebrew phrase is informed by 1 John 3:12, which refers to the Cain and Abel episode and notes that Cain’s sacrificial deeds were “of evil intention”. Augustine concludes that Cain “gave to God something belonging to him [that is, to Cain], but gave himself to himself”. Put another way, despite the act of sacrifice, Cain failed to offer himself to God.

In contrast to Cain, Abel can be seen as the progenitor of Christian sacrifice, who offers up himself in his visible sacrifice, which was “the sacrament, the sacred sign, of the invisible sacrifice” of his own self. That Abel’s pleasing sacrifice ultimately was an offering of himself is proven later in the narrative as Abel himself becomes a bloody sacrifice at the hands of his elder brother Cain.

The theme of sacrifice bleeds over into the theme of martyrdom almost imperceptibly. As Augustine says of Christian sacrifice:

We sacrifice blood-stained victims to [God] when we fight for the truth ‘as far as shedding our blood’.

The Christian martyrs, hoping in the city of God and suffering persecution even unto death, find their symbol and historical origin in righteous Abel, who was “the first to display a kind of foreshadowing of the pilgrim City of God; showing that it was to suffer unjust persecution at the hands of wicked and, in a sense, earth-born men”.

As mentioned above, Abel’s vocation does not terminate at his death, but continues as Seth carries on his brother’s holiness. This again reinforces the eschatological dimension of this allegorical reading of Cain and Abel. For Augustine, the death of Abel foreshadows the vocation of the Christian martyr. The martyrs, in recapitulating the fate of Abel, can die in hope that they will be succeeded by Sethites in future generations: the Church will be established in history as a result of their sacrifice.

The Church is established not despite persecution and martyrdom, but precisely because of it: Augustine states that the martyrs of the past “contended for the truth as far as the death of their bodies, so that the true religion might be made known and fiction and falsehood convicted”. With this dynamic perhaps in mind, Augustine notes the deaths of these martyrs “brought shame upon the laws forbidding Christianity and brought about their alteration”.

This motif also relates the narrative of Cain and Abel to the crucifixion of Christ at the climax of the biblical story. By way of “prophetic allegory”, Augustine finds that Cain “symbolises the Jews by whom Christ was slain”. Augustine briefly alludes to his previous allegorical treatment of Cain and Abel in Contra Faustum (12.10). In that work, he again notes the “post-mortem” effect of faithful blood being shed:

For the blood of Christ has a loud voice on the earth, when the responsive Amen of those who believe in Him comes from all nations. This is the voice of Christ's blood, because the clear voice of the faithful redeemed by His blood is the voice of the blood itself.

For Augustine, the martyr is active in his martyrdom: he fights for the truth to the point of shedding blood, and thus establishes better conditions for the pilgrimage of the heavenly city in future generations.

Cities founded upon blood

In the biblical text, after Cain expresses fear that his own blood will be sought for murdering Abel, and God gives Cain a mark of protection, Cain nonetheless establishes his own city. It is suggested that this first human city is built with something of a guilty conscience: under the foundations of this city is the blood of an innocent man.

Augustine’s relating Cain to the earthly city, both as its symbol and its first founder, adds some colour to his more sweeping critique of the earthly city found throughout The City of God. One of Augustine’s earliest condemnations of earthly Rome in Book I is that it is “a city which aims at dominion, which holds nations in enslavement, but is itself dominated by that very lust of domination” (The City of God). Very similar language appears in Augustine’s discussion of Cain in Book XV: he symbolises the city that reigns “in the enjoyment of victories and an earthly peace, not with a loving concern for others, but with lust for domination over them”.

Especially fascinating is Augustine’s discussion of the story of Cain and Abel as an “archetype” which was later answered in the legendary story of the founding of Rome, in which Romulus murdered his twin brother Remus in the course of establishing his city. Augustine thinks it fitting that Rome, “the city which was to be the capital of the earthly city” should have been founded in a way that so strongly resembles the founding of Cain’s city in the book of Genesis. This powerfully presents the way in which Augustine’s allegorical readings inform not only his reading of Scripture, but also his reading of the world’s history.

It is as though Rome still has the bloodstains of innocent Remus on its conscience all these centuries later, even as Cain was haunted by the voice of the blood of righteous Abel as he established his city. Cain’s city always has this terrible murder of the innocent at its foundations. Likewise, the city of Rome whose downfall Augustine has discussed at length in The City of God, is forever haunted by this fundamental injustice that characterises it.

The key difference that Augustine draws between the story of Cain and Abel and the legend of Romulus and Remus is that the former represents the conflict between the two cities, and the latter represents the internal conflict of the earthly city. Augustine attributes this to the fact that the earthly city seeks earthly glory, power and other earthly goods, all of which are inherently zero-sum:

Anyone whose aim was to glory in the exercise of power would obviously enjoy less power if his sovereignty was diminished by a living partner.

Here another element of the diptych between the two cities is made out: like Cain, the earthly city is willing to make war “for the sake of the lowest goods” , but it can never truly achieve the peace that it seeks. The earthly city is inherently fractious within itself so long as it seeks earthly goods. Its social life is fraught with “wrongs, suspicions, enmities and war”.

By contrast, Abel’s legacy (via Seth) is a commonwealth whose citizens “make use of this world in order to enjoy God” in whom is their true and eternal felicity. There is an inextricably social element to Augustine’s vision of the heavenly city and its delight in ultimate good. He takes it to be an absurdity that the city of God could have made its first start or achieved any progress “if the life of the saints were not social”.

This is one of the paradoxes of the Cain and Abel narrative that Augustine seems to be playing with: though Cain founds a city, he will never truly have a city in the final reckoning. By contrast, Abel set his hopes upon the only Supreme Good around which a true commonwealth can be formed; though Abel died alone, he will not be found without a city.

Conclusion

The passing details in biblical texts are, for Augustine, potentially full of meaning. As Thomas Williams notes:

Augustine finds a great deal in his chosen texts — partly because, being thoroughly convinced of their divine authority, he expects to find a great deal in them. (Thomas Williams, ‘Biblical Interpretation’ in Cambridge Companion to Augustine, ed. Eleonore Stump and Norman Kretzmann)

The story of Cain and Abel, coming early in the biblical narrative, is for Augustine the seedbed of many of the themes that come to full flowering over the course of the Biblical narrative, and even into extra-biblical history. Crucially, this approach to reading the Scriptures allows Augustine to see the entire world in their light.

The small details of the text matter to Augustine, and he is attentive to the way that Scripture alludes to previous episodes in later history, using basic elements like diptychs, or by connecting two characters via things like blood; for example, Abel and Christ. Even a character’s name is a clue to his significance, notwithstanding Augustine’s sometimes unsuccessful attempts to discern their precise meaning.

For Augustine, an allegorical reading of Scripture is not mere “spiritualising” of a text, but rather, the spiritual meaning of the text includes the concrete realities of the history, which is the story of the pilgrimage of the heavenly city of God.