I’ve very much enjoyed a recent reflection by Andrew Noble on our use of headphones and its implications for our capacity to love:

Recall again the newborn girl. As she grows into a toddler, she will begin playfully testing her perception of sound. By cupping her hands on-and-off both ears, for example, she receives a sound like that of a rushing wind. For the first time in her life, she will control her own perception of the sound around her. And before long, she will be able to fully suppress the auditory world through not only a screaming slammed door in the midst of a temper-tantrum, but also in the wearing of noise-cancelling headphones. She controls the world. She controls her loves.

I commend the entire piece to you.

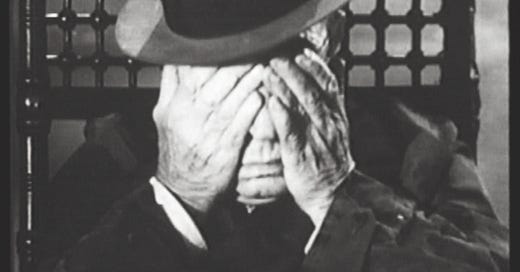

One of the things Noble’s piece brings out is the significant difference between the acts of hearing and seeing. The eye allows one to exercise a certain amount of control over that which it sees. The eyes render judgment, and things are judged good or bad in one’s eyes. Things—even people—can be pinned down and inspected under the eye, like specimens of insects under a microscope. Samuel Beckett played with this idea in his short silent film, Film: the main character played by Buster Keaton spends the film seeking to escape the gaze of all eyes, and all things that look like eyes.

The ear, however, is receptive and passive. While there are such things as “eye-sores” placarded in one’s face that one would rather not see, it is generally true that to some extent you can avert your eyes from seeing things you do not want to. God gave us eyelids, but not ear-lids: so, the ears are more easily subjected to whatever is nearby them. As Joseph Minich writes, “In vision, I experience the world as that upon which I actively gaze. In sound, I experience the world as acting upon me.”1

Hearing connotes obedience, and being subject to something. Hence, the great command to Israel is that they hear the Lord—and it is perhaps significant also that Moses recalls the event at Mount Sinai, as one in which Israel heard the Lord’s voice thundering from the mountain, though they saw no visible form (Deuteronomy 4:12) In the Psalms, the Lord’s servant emphasises his posture of obedience by speaking about his ears:

Sacrifice and offering thou didst not desire; mine ears hast thou opened… (Ps. 40:6)

With this in mind, in the last few years I have generally taken to listening to Scripture on audio, rather than sitting and reading it in print. Of course, I have no objections to reading a Bible, but both for theological and practical reasons, I have found the practice of listening to Scripture far more fruitful. The theological reasons I have gestured at above: the mode by which the Word of God primarily comes to us corresponds to our sense of hearing, not of seeing, and I have found that it is easier to attune one’s self to the intertextuality of the Scriptures when one hears similar turns of phrase repeated. I also find that I engage with more Scripture in this way. When I use my eyes, I am wont to stop and study the text regularly.

Practically, I have found the most ideal time for this listening is in my walk to work each day: I have a nice fifteen-minute walk down North Hill into the centre of town here in Armidale, which usually allows for my listening to three or four chapters of Scripture. But in light of Noble’s reflections, this does create something of a problem for me: in my habit of Bible listening, I necessarily isolate myself from the real world that immediately surrounds me. While the sounds I am taking in are wholesome and good, have I chosen the greater good, all things considered?

I should say that rather like the idea of having serendipitous meetings in town with people I know, and Armidale is a cozy enough city that you can expect this kind of thing quite frequently. And, truthfully, I do not much like the idea that our public space might become exactly what it would become if each individual was wearing headphones while out and about: a maelstrom of separate private spaces together in public. Part of the deal of being in public is that others can interact with you, make reasonable demands upon your attention, and engage with you as one out there to be engaged with. My wearing earphones out and about indicates to others that, notwithstanding my bodily presence, I am not really here, and I am not available to them. I say, in effect, “I am alone in my own room with the door closed. Please stay away.”

The habit that is formed over time, as Noble suggests, is that the auditory channel by which our affections for people and place are formed is sealed off and protected, and the things and persons that I grow to love are not those given to me, but rather, those that I have chosen:

Building on this, with the quality of headphones available today, we have more ability to resemble personal presence with those who are distant from us. But this artificial or re-presented interaction comes at a cost. In doing so, in listening to far off professors, politicians, and podcasters, we sacrifice opportunities to grow in physical presence and proximal love.

Noble is careful not to dismiss headphones as an evil in principle, but he is right to warn us of what kinds of habits they form, and therefore, what kind of people they make of us.

A few days after I first drafted this piece, it came to pass that I damaged the tip on one of my AirPods while trying to clean them out. The replacement tips are cheap to acquire, so that isn’t the end of their life just yet, but we have now had a few days without them available for our use. I expect we will live, and we might even live happily.

Bulwarks of Unbelief: Atheism and Divine Absence in a Secular Age (Bellingham, WA: Lexham), 2023.