At the climax of Psalm 130, the psalmist turns, as it were, from his own experience of confession and waiting for the Lord to address the congregation of Israel. The nation is being invited to see in the experience of this individual Israelite something that they can participate in as a nation. Israel is assured that if he cries out to the Lord from the depths, the Lord will hear him and send him his Word to redeem him.

Israel in the depths

The national history of Israel is a story of death and resurrection, of exile and return, of plunging into the depths and returning to the land. Psalm 130 has used the motif of the great deep from the creation narrative as the setting for the psalmist's confession. By implication, he is seeking to be brought up to the dry land. Likewise, there is a creation-like movement in the psalm from evening to morning.

These same creation motifs are used throughout the Scriptures to tell the story of Israel as a polity. Just as God brought the dry land up from the deep darkness in the beginning, so also he formed Israel as a new creation, bringing him up and out from the raging sea of the Gentiles during the exodus and established him in the land of Canaan:

But I am the Lord thy God, that divided the sea, whose waves roared: The Lord of hosts is his name. And I have put my words in thy mouth, and I have covered thee in the shadow of mine hand, that I may plant the heavens, and lay the foundations of the earth, and say unto Zion, Thou art my people. [Is. 51:15-16]

But as the kingdom of Judah descends into wickedness and apostasy, God sends the Gentiles like floodwaters to "de-create" the land, until they are formless, void and dark once again (Jer. 4:23). So Israel finds itself in the depths and under darkness, with no hope within itself of returning to dry land and light.

In this context, we can that Daniel’s prayer of confession in Babylon is a direct parallel to the psalmist’s prayer from the depths, in which he calls upon the Lord to hear his voice. As Israel sits in the depths of exile, Daniel asks God to “hear the prayer of thy servant” and “incline thine ear, and hear” (Dan. 9:17-19). Unrighteous Israel cannot persuade God to return him from captivity by appealing to any of his merits or virtues; he can only cling to the covenant love and mercy of Yahweh, who promised to rescue them from captivity if they confess their iniquity (Lev. 26:40-42; Deut. 30:3).

Waiting for the Word

Just as the psalmist’s confession is followed by waiting for the Word of the Lord to come and declare forgiveness, so also Israel found itself in a long season of waiting for the Word to come to them. Throughout the prophecy of Isaiah, the Word of God is shown to be sent forth to declare forgiveness to Jerusalem and to bring his people back from bondage (Is. 40). This Word comes to Israel through heralds and preachers whose beautiful feet ascend the mountains to preach good news (Is. 52:7). We should not miss that the Word is closely associated also with God’s Servant; the Word is a Person sent forth to perform God's will. When the Servant-Word goes forth, God promises to uphold him and ensures that he will prosper in his mission (Is. 55:11, 48:15-16). The psalmist has hoped eagerly for the Word like a watchman; so also the Servant-Word is seen approaching by watchmen, who lift up their voice in exultation as they see the Lord returning Zion from exile (Is. 52:8).

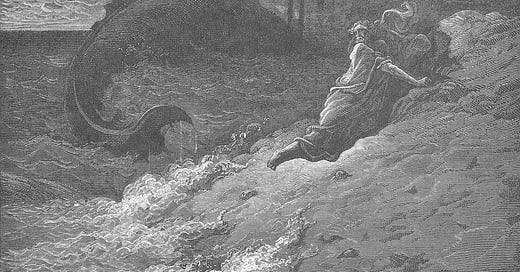

It is not difficult also to see similarities between the experience of the psalmist and the experience of Jonah. Jonah’s prayer in the belly of the fish draws on this same map from the creation narrative: God is in the heavens and the sinner is in the dark depths of hell itself. Jonah declares that even from the depths, his prayer reached up to God’s temple on high (Jonah 2:2, 7). The fish then spits up Jonah upon the dry land, and the Word of the Lord comes to him a second time (3:1).

Buried and raised with Christ

As John teaches most clearly, Jesus Christ is that Word made flesh, sent by the Father in the fulness of time to restore Israel from their death in captivity—and not only Israelites, but all the sons of Adam who have been exiled from God's presence since the fall.

Christ, like the psalmist, is the individual in whom the experience of Israel was fulfilled. Thus, it was necessary for Christ to be exiled to Hell, and to rise again on the third day: Jesus calls this matrix of events “the sign of Jonah” (Matt. 12:39-41).

Once risen, Christ commissioned his apostles to preach the forgiveness of sins to Israel, and indeed, to all the nations. Peter tells his Israelite readers that the Word of comfort spoken of in Isaiah 40 is "the good news that was preached to you" (1 Peter 1:25, ESV). Likewise, Paul declares that as the apostles preach the gospel, Christ himself is being presented to the nations:

How then shall they call on him in whom they have not believed? and how shall they believe in him of whom they have not heard? and how shall they hear without a preacher? And how shall they preach, except they be sent? as it is written, How beautiful are the feet of them that preach the gospel of peace, and bring glad tidings of good things! [Rom. 10:14-15]

The hearers of gospel preaching do not only hear about Christ, but they hear Christ himself. John Murray observes that "Christ is represented as being heard in the gospel when proclaimed by the sent messengers. The implication is that Christ speaks in the gospel proclamation" (Murray, 386, emphasis added).

Christ is the last Adam, formed from the dust, from the earth which came up out of the water. He is the true Israel who was exiled into Hell itself, and was raised up from of the depths for our justification. By the mouths of his apostles, and by the mouths of gospel preachers to this very day, Christ preaches forgiveness of sins to the nations and redeems them of all their iniquities.

Bibliography

John Murray, The Epistle to the Romans, (Glenside, PA: Westminster Seminary Press), 2022.